Merton's Silent Revolution

I just re-read Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain. This is an autobiography written early in life by a more or less normal man who became a monk. I re-read it because when I read it as a young man, I had no idea what it really meant. Now, as life and experience have moved me along, I have some sense of what this book means. And thought I would share this with you.

This is not a book report, more my impressions and reactions. As a book, it’s somewhat like Augustine’s Confessions. Young man, dysfunctional family, depression, gets in trouble, very talented, misuses talent, great pride and aspirations, sees the emptiness of it, gets a sense of religion, falls away from religion, is drawn back to it, is repelled by people within it, persists, becomes a monk, and is beset with temptation, struggles, recommits and dies a monk and a fallible human.

If that were all there was to it, this book would not be a classic.

But it is a classic. Why? It does several things at once time. It subtly shows our intermittent callings by the Holy Spirit even in the midst of a chaotic, pleasure-seeking irresponsible life. It shows the subtle growth of hunger for God even as we are motivated by the empty promises and deep fears of the ordinary lives we lead. And surprise! It shows the more we eagerly seek God, the more the Opposer, the Devil works to turn us away. The Opposer uses our scrupulosity and inertia, our fear of change, to give us reasons to turn away from God, to stop trying. You may have experienced this yourself.

In short, Merton’s book illustrates a sort of Purgatory on earth. A central truth seems to be that we have to fail at our own efforts before we can let God make us happy humans.

In a powerful, subtle way it is also an update of Dante Alighieri’s Purgatorio, the middle book of three books that make up Dante’s Divine Comedy. Dante wrote Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso around 1300 AD. Dante gives a powerful word picture of Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. Merton never mentions Dante or the Divine Comedy except in the title, Seven Storey Mountain, but the Seven Storey Mountain is Purgatory Mountain.

What is Purgatory?

Purgatory traditionally refers to a “place” or time after death when the souls of those who died destined for Heaven, but still needing purification, are given the opportunity to atone. Purgatory gives departed souls the opportunity to undergo the final cleansing of sin so they are fit to enter Heaven.

Some believe in a Purgatory; others do not. Whether it exists in the after life or not is not the issue here. Merton clearly is referring to the Purgatory we go through in this lifetime, an experience we can all relate to. Remember, Jesus said, “The Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.” The Kingdom is here and now. We just have to look carefully.

The Mountain of Purgatory, and our personal mountain, has seven levels as you wind from bottom to top. Dante described how Hell and Heaven also have levels, levels of sin or virtue similar in many ways to the seven storeys of Purgatory. Like Merton, let’s focus briefly on the seven storeys of Purgatory. Merton went through each of these during his lifetime, and so do we.

The lowest level in both Hell and Purgatory is for the sin of Pride. Dante tells us how the proud in Purgatory carry enormously heavy stones and are purged of these stones only through praying for humility. The healing, purgative Beatitude is Blessed are the poor in spirit. We are to recall the perfect humility of Mary, “I am the handmaiden of the Lord.” Merton tells how his own pride - and the other six sins - led him off the path. Seven Storey Mountain relates how after each falling away Merton was drawn back onto the upwards slope. Rather than retelling Merton’s story, let’s consider Dante’s description of the other storeys of the Mountain Purgatory.

The second storey is Envy. Dante describes how the envious have their eyes sewn shut and wear grey cloaks. They are purged through the grace of Generosity, and the prayer to love ones enemies.

The third storey is Wrath. The wrathful, angry are blinded by thick acrid smoke.

These first three sins are sins of encroachment, sins that affect others. Merton goes through each of these in turn.

The fourth, middle level sin is more passive, Sloth. Sloth does not mean laziness. The proper word for Sloth is “Acedia.” It is not a lack of activity, it is a deficiency of Love, an indifference. Those on the slothful, indifferent level of Purgatory are engaged in ceaseless activity – but feel ceaseless sadness. The purgative of sloth is Zeal, zealous love of God and compassion for others. Hmmm. Do we wonder why we are sometimes depressed even though we are engaged in all these good works?

The next three storeys of the mountain are different. These are sins of “too much of a good thing.” Excess of good is its own sin. Covetousness, is different from Envy. The covetous are eager to possess something for themselves, without regard for what others have or don’t have. Extravagant ambition is a form of covetousness. The Covetous are lying flat on the ground, face and eyes down.

Next up is Gluttony. Gluttony is the excessive love of good things. Here the prayer should be, “Oh Lord, open my lips, that my mouth might declare thy praise.” Quite different from, “gimme that.”

The highest, last storey of the seven storey mountain is Lust. Lust is too much love, too much and wrongly expressed. In Dante, lust is presented as our greatest challenge, and the last sin to be overcome before readiness for Heaven. Lust catches us at the point of departure somehow of the soul from the sensual body. We are at the same time sensual creatures which lust, and creatures with souls which love. When grace converts our self and our body, lust turns to love. At the top of Mt. Purgatory, the lustful are confronted by a wall of flame. The cure here is to seek the chastity of Mary and the contemplative attitude of Rachel, Jacob’s most beloved wife.

The book recounts how Merton experienced his journey up the seven storeys, his approaches and fallings. He finally became an avowed monk. And continued to struggle up and down the mountain. But Merton, with clear eyes, recognized the reality of Mt. Purgatory and had an epiphany. Monks in religious life had replaced deep prayer and contemplation of God with ceaseless activity.

Mertons Contemplative Revolution

At the end of Seven Storey Mountain, Merton ignited a world-wide religious revolution with his Epilogue. It's been rolling ever since. Merton didn’t start this revolution; it was the Holy Spirit. The Spirit slammed Merton with a hunger beyond traditional, obedient, rule-oriented religion. A few quotes:

“We are born with the thirst to know and to see Him…What a relief it was for me, now, to discover …that no idea of ours, let alone any image, could adequately represent God.… How many… stand and starve at the doors of the banquet…. This means, in practice, that there is only one vocation. Whether you teach or live in the cloister or nurse the sick, whether you are in religion or out of it, married or single, no matter who you are or what you are, you are called to the summit of perfection: you are called to a deep interior life perhaps even to mystical prayer, and to pass the fruits of your contemplation on to others. And if you cannot do so by word, then by example.”

The revolution is the practice of deep prayer, the practice of still, quiet, contemplative prayer.

The Holy Spirit had roused the Church earlier. The movement of the Holy Spirit is often resisted by religious authorities. I think it is because the Holy Spirit doesn’t play by human rules. As the new Pope Francis says, “God is a God of surprises.”

In the Jewish Scriptures, Saul, before he became king, was anointed by the prophet Samuel, was moved to ecstasy by the Spirit. The religious critics sneered, “Is Saul among the prophets?” King David accompanying the Ark of the Covenant into Jerusalem, was moved by the Holy Spirit to dance wildly during the procession. His wife, Michal, sneered at him for exposing his underwear to the servants. This is a literally true story, but also a parable. David represents the movement of the Spirit in the Church. Saul’s daughter, Michal, now David’s wife represents traditional religious authorities.

John the Evangelist in the first century, the Desert Fathers in the fourth, the Celtic Contemplatives in the eighth, Theresa of Avila and John of the Cross in the sixteenth century, each at the Spirit’s direction fired a contemplative birth and rebirth within the Church. And each was sometimes violently rejected by the Church authorities at first. But the Spirit persists. And in the 1950s the Spirit was working through Merton.

Merton and The Holy Spirit

Merton first opened his eyes to the Holy Spirit working in his life in his final years at Columbia, when he read Eastern mysticism and William Blake. He began to recognize the power of silent contemplation, of resting in the presence of God. Dante had a guide as he climbed the seven storey mountain of Purgatory. Virgil, the great Latin poet was at his side explaining and teaching Dante what he was seeing. Virgil of course is a metaphor for the Holy Spirit. Merton was guided up his Mountain by the Holy Spirit. And the Holy Spirit wants to guide us up ours.

Today in the West, a powerful movement of the Holy Spirit is called the Contemplative movement. This movement adds a dimension to our Christian life of Liturgy, Scripture study, Good Works in help of others, and traditional prayer using words.

Merton in his epilogue reflects on the "new" dimension of emptying ourselves of self and listening for the voice and action of the Holy Spirit within. Deep, silent, attentive prayer, Merton was now a Trappist monk at a Monastery in the hills of Kentucky. He reflects that of all religious, monks should be the most contemplative, seeking God in the quiet and stillness of prayer. Yet, Merton saw the monks engaged in ceaseless activity. All good works, gardening, making cheese, bread, preparing food, cleaning, regular waking and praying. Even writing and teaching. Merton was personally weighed down by the tasks of writing and teaching assigned by his superiors. His question: Are the religious sliding back down the mountain?

But, Merton begins to discover and teach balance: Balance? Not giving up, but adding and balancing. The three-legged stool of action in help to others, ritual, liturgy and spoken prayer in submission and transformation, and adding the often missing third leg of the stool-– deep, attentive silent prayer in contemplation of God.

Resistance to Contemplation

Contemplation’s critics within the Church rise as always to meet this threat to orderly and rule-bound religion. Contemplation moves in unpredictable directions, just like the Holy Spirit. So resistance boils up. "That's just not how we do it." A religious life doesn't always mean meeting the unpredictable with Gospel welcome. The "religious" life can be its own deadly trap. Our sins go along with us, just dressed up in religious vestments and robes. Instead of plain old Pride, Envy, Wrath, we can see Spiritual Pride, Spiritual Envy, Spiritual Wrath. These resist change.

Look at the excesses of the Taliban, the rigidity and wrath of Sharia – and in the West, the wrath and indignation of conservative Catholics at the Pope for suggesting mercy and acceptance, rather than condemnation and exclusion of homosexuals and the remarried divorced. Or, the wrath and pride of many conservative Protestants at anything less than literal interpretations of thought and behavior.

Why this resistance by the orthodoxy? I think it is fear. Fear is usually at the root of all the Seven Deadly Sins. Fear is clearly the root of Pride, Envy and Anger. But, perfect love drives out fear.

Merton was alarmed at the focus on activity and obedience in the monasteries. In Seven Storey Mountain and throughout his later works, he urges the religious to de-emphasize actions alone and open up to silent contemplative prayer. Following on Merton, John Main in England and Canada, and Thomas Keating, Basil Pennington and William Menninger in the United States launched contemplative movements. From the monasteries, the movement reached out to the lay public, and is now being practiced in mainline Protestant and Catholic congregations around the world. It's still being met with passive aggressive resistance. Contemplative groups meet at church ... in the basement and without the pastor. It's mentioned in the bulletin ... but not from the pulpit. It's a revolution ... but kept at bay.

Is Contemplative Prayer for Everyone?

Contemplative prayer is not for everyone. Ultimately, contemplation is a gift of God and a deepening of relationship with God. We can’t know whether this gift is for us if we don’t give the Holy Spirit a chance. We are urged to aim for the higher gifts. It’s easy. All you have to do is sit still. This is hard for many of us.

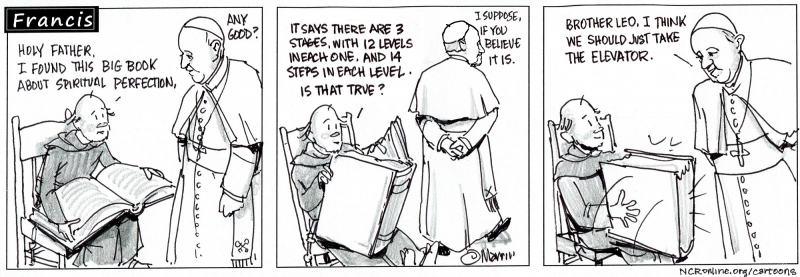

Contemplation and the direct experience of God is freely available. “Come to the waters. Eat and drink freely, without price”, says Isaiah. Our path up the seven-storey mountain of this life might be easier if we were to take the gentle, contemplative elevator.

This is a congregation of helps and music, full of good works. We have that leg solid. One hour of liturgy and verbal prayer on Sunday is not enough. I am so happy about the increasing number in Bible Study. There is more depth to scripture than what we learned as children and teens. It’s good to see we are still hungry to grow spiritually. And, this hunger is the beginning of the path to contemplation. We live Merton's Seven Storeys. He calls us to recognize when the Spirit is calling to us to pay attention. Listen up. It's a revolution.

Q&A

Next Step?

Step One: YouTube has a brief Intro of Thomas Keating’s Centering Prayer Guidelines. Google, “Thomas Keating Larry Weiss”.

It’s less than eight minutes long.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3IKpFHfNdnE

Step Two: Up to you and the Holy Spirit.